A Timeless Pulitzer Prize-winner: The 1619 Project

Pulitzer Prize-winning stories often fade from our memory, because news is fleeting. But The 1619 Project will stand the test of time.

Pulitzer Week continues, and no list of this year’s winners would be complete without The New York Times Magazine’s The 1619 Project.

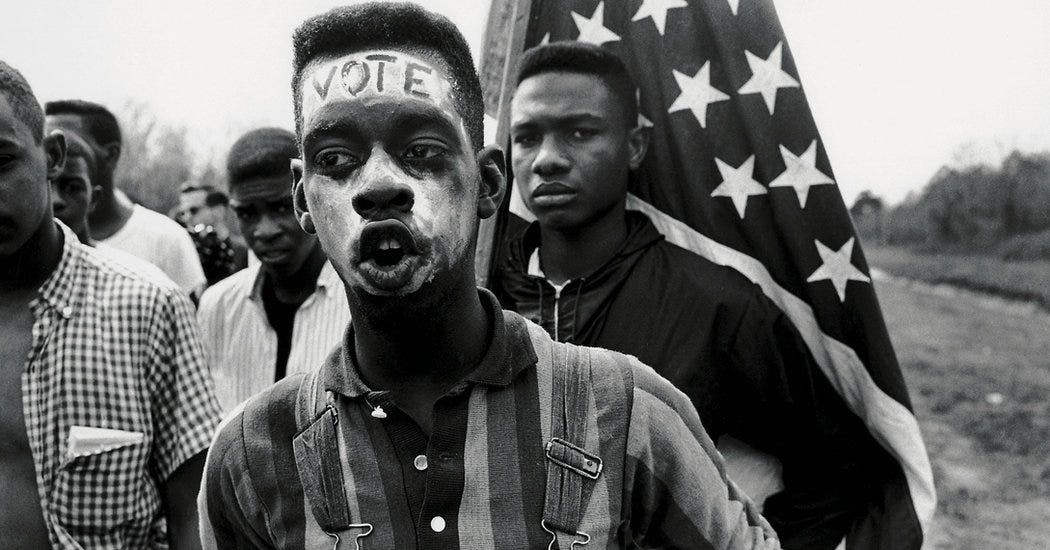

Nikole Hannah-Jones conceived of the project, and she won the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her lead essay, “America Wasn’t a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One.”

Hannah-Jones starts her essay close to home:

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

After she described her father’s upbringing in a sharecropping family on a Greenwood, Mississippi plantation, his voluntary service in the U.S. Army, and his failure to ever get ahead in life despite dedicated hard work, she writes:

So when I was young, that flag outside our home never made sense to me. How could this black man, having seen firsthand the way his country abused black Americans, how it refused to treat us as full citizens, proudly fly its banner? I didn’t understand his patriotism. It deeply embarrassed me.

So much of the beginning of her essay resonated with me, and it went deeper than just her masterful prose. It transported me back to Mississippi. Before I ever settled there, I remember vividly the outrage I felt when I was pulled over in the middle of the night just outside the city of Greenwood. I was on the way back to Cleveland, Mississippi, with my friend and instructor during my Teach For America orientation summer. He taught our courses every afternoon after we’d finished teaching our summer school classes. He noticed my clothes day in and day out, and he always had something nice to say about them; he rightly deduced that I’d be game to go shopping. Since he had no car, he’d asked me if I’d be willing to drive, and, of course, I was thrilled to get out of Cleveland for a day. After a day at the mall, we went to a nice steakhouse in Jackson; we ate our steaks and washed them down with non-alcoholic drinks, sweet tea for me and Sprite for him.

On the road, he reclined the passenger seat and fell asleep. I was pulled over by a cop sitting off in the fields along the two-lane highway. The cop approached the window, asked if I knew I’d been speeding, and after I answered, he asked me to get out of the car. Before I did, he asked if I had any weapons in the car. No, I said. He walked me to back of my SUV, asked me to put my hands on the glass, and he kicked my feet apart with his foot. He asked again if I had any weapons on me (“Anything that’s going to cut me or hurt me?”), and again I said no. I had graduated law school only a month earlier, though I didn’t need the degree to know I was being subjected to an unreasonable search. There was no probable cause to ask me out of the car; no probable cause to search me. But I didn’t raise this point. I simply did as he asked.

After he patted me down, he asked me if I’d been drinking. I answered him honestly: no. If he’d seemed the type to care, I’d have told him that at that point in my life, I’d never had a drink, and I’d have still been telling the truth. Then he asked about my friend, who’d remained reclined and dozing after I’d pulled over. “What about him? He been drinking?” I answered him honestly again: no. But what difference would it have made? Had he been drunk off his ass, I’d have been doing exactly what responsible adults are expected to do. But when he asked, I knew he was grasping for straws.

He asked me to get into the front seat of his squad car. I remember he had the air conditioner blasting to combat the sticky, humid Mississippi Delta summer night. I sat on my hands and fought to keep my teeth from chattering. I remember how bulky he looked in driver’s seat, with his tactical vest on and how he had to adjust it like a football player repositioning his shoulder pads by pulling down on the chest. I remain convinced that he wanted me in the close proximity and contained space of the car so he could have more easily smelled alcohol on my breath, because on some level (not yet rising to subjecting me to a field sobriety test) he didn’t believe me. I remember the tapping of his keyboard as he banged out my citation. I remember the printer under his dash spit out the ticket, how it ran forever as if printing out an old-fashioned scroll, and how he sent me on my way.

I have serious reservations about how that encounter might have turned out if my friend, who was a black man, had been driving my car, or if he’d been reclining because he was actually sleeping off multiple beers from the steakhouse instead of sleeping off exhaustion from instructing recent college grads on how to be the best possible teachers they can be. When Hannah-Jones talked about Mississippi and how cavalierly “justice” was administered, I thought of how I seethed with anger after that encounter, and how I honestly didn’t know the half of things.

Even more than that memory, Hannah-Jones’s essay made me think of an observation I made during a Holmes County Board of Supervisors’ meeting. I sat up on the dais as the county attorney, and I was the only white person on the dais and in the room. The meeting began with a prayer, as it always did. Instead of focusing on the Divine, I was focused on the gathering of Holmes County natives with their heads bowed. As the prayer continued, exclamations of support and affirmation rang out around the room. It also stood out to me, as a prayer had always been a somber and somewhat solitary event in the Southern Baptist churches of my youth. In Lexington, the prayers were communal events where numerous people contributed to the prayer out loud at the same time. In the supervisors’ meeting, the voice that stands out to this day in my memory was that of the board president Mr. Young and his steady stream of “Yes, sirs” said with a syrupy Mississippi drawl and without the terminal r — “Yes, suh; yes, suh.” He’d join the speaker’s giving of thanks — “Thank ya, Thank ya, suh.” Sometimes he’d just grunt his approval and agreement, no words needed.

As I listened, I couldn’t help but smile. It was so different from what I’d grown up with, but, my goodness, how I loved to hear it. It was inspirational in its way, such a simple thing, I know. But it had more to do with the atmosphere that was created by the prayer itself, an atmosphere those in attendance sought to create.

In that moment, I sat there and marveled, a bit dumbstruck. The poverty in Lexington is breathtaking. The town is defined in so many ways by what it doesn’t have. The leaders are constantly trying to do more with less. I saw incredible difficulty in the lives of many residents up close from my time as both a teacher and a lawyer. Yet the residents, and particularly the black residents, were some of the most faithful, God-fearing people I’d ever met. They asked for God’s blessings, and they expected them. They thanked God, and they meant it. And I had to wonder: Why? How? Look around you, people! Do you think anyone is hearing your prayers? Is this what your faithfulness has earned you? Because I don’t see it.

I don’t intend to attempt an answer to those questions; in fact, I’m not even proud that I asked them in the first place. But like Hannah-Jones, I realized there’s more to it than meets the eye; she writes:

I had been taught, in school, through cultural osmosis, that the flag wasn’t really ours, that our history as a people began with enslavement and that we had contributed little to this great nation. It seemed that the closest thing black Americans could have to cultural pride was to be found in our vague connection to Africa, a place we had never been. That my dad felt so much honor in being an American felt like a marker of his degradation, his acceptance of our subordination.

Like most young people, I thought I understood so much, when in fact I understood so little. My father knew exactly what he was doing when he raised that flag. He knew that our people’s contributions to building the richest and most powerful nation in the world were indelible, that the United States simply would not exist without us.

There was a journalistic (and life) lesson embodied in this project as well: Don’t be dissuaded by the little voices of doubt in your head that say, “If this were an idea, someone would have had it by now.” Though the subject matter is older than our country, The 1619 Project was celebrated not just for its scope but for its treatment of a subject too rarely discussed. But the topic has been sitting here for the taking, waiting for a journalist to come along and propose such a massive undertaking; it didn’t happen until Nikole Hannah-Jones did it in 2019. It’s sad that it’s taken us this long, but thank goodness she came along and gave it to us at all. Better late than never.

It was also a worthy Pulitzer Prize recipient when you consider the conversations and debates it sparked. It got people talking, and it didn’t simply want your clicks and newsstand purchases; it wanted to advance the discussion of slavery in this country and how it still affects everything that happens here. Upon its publication, the project, and this essay in particular, drew criticisms from critics and historians. Rather than letting the discourse devolve into a shouting match, The New York Times Magazine responded admirably. If The New York Times Magazine was guilty of overstating its intention despite warnings, it should be commended for not letting it stay that way.

It engaged in thoughtful conversations. It made us think. It was responsible in its handling of the debate that it sparked, and, honestly, we couldn’t ask for more from our journalists.

Read Nikole Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay here:

The 1619 Project: America Wasn’t a Democracy, Until Black Americans Made It One | The New York Times Magazine

If you liked what you read, please sign up, follow me on Twitter (@CaryLiljohn06) and then forward to friends to help spread the word.