In Support of the Marion County Record

Freedom of the press comes under fire in small Kansas town, after newspaper is raided by police.

Every now and then, I come across a story that resonates because of how easily it could have been my own. That’s how I felt reading the ongoing drama with a tiny Kansas newspaper that was raided by the town’s police department. It felt like it could have been a reality that my colleagues and I at my Wyoming newspaper could have faced.

Now, it bears stating that I actually thought very highly of the police and sheriffs in Gillette, Wyoming. They were, by and large, no great fan of us at the paper, but that didn’t make them outliers; it made them just a community member.

But that’s what I’m talking about. That rabid, antidemocratic impulse that sees the local newspaper not as a force for good, a watchdog in the community, a chronicler of moments big and small but rather a conniving extension of the dreaded mainstream media full of socialist and communist sympathizers who have the audacity to put their stories on the internet and charge for access to them. In short, the enemy.

That was the environment into which I stepped when I landed in Wyoming in 2020. Four years of President Trump’s railings against the media, calling them liars and terrible people, had, unsurprisingly, trickle-down effects for residents of a county that loved Trump. They also had a superior class of newspaper for the size of their town, and it was nothing remotely like the boogeyman of liberalism that they so desperately wanted to believe.

I first read a detailed account of the raid on the Kansas newspaper in Judd Legum’s newsletter Popular Information.

His account begins on a sadder, personal note to the story, separate from it’s implications for press freedom and democracy:

"These are Hitler tactics, and something has to be done."

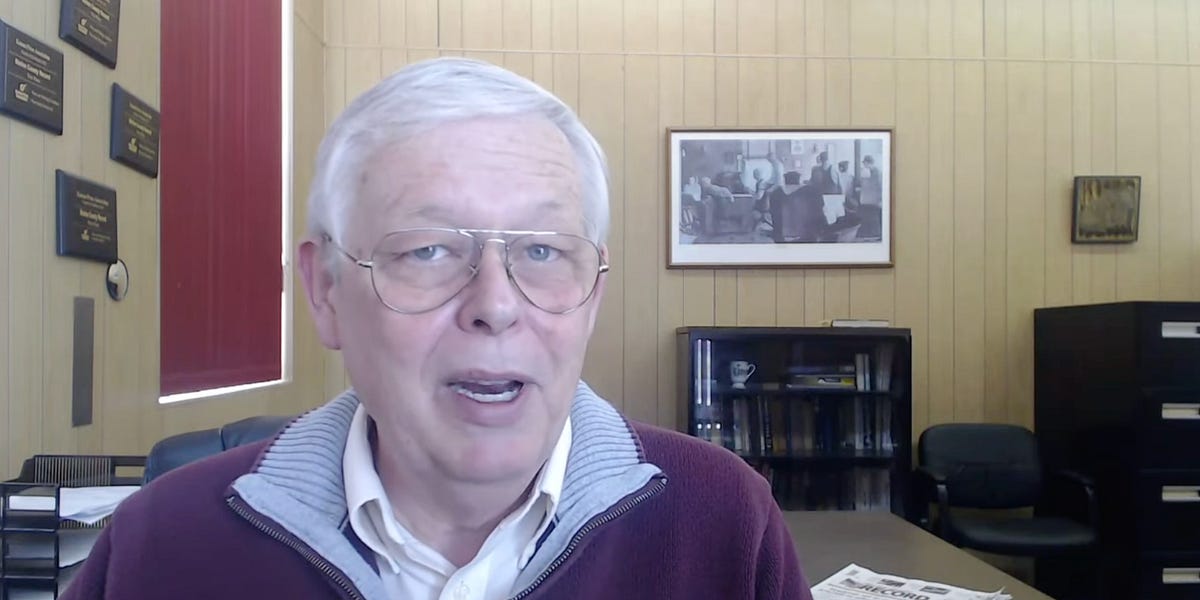

Those were the words of 98-year-old Joan Meyer, the co-owner of the Marion County Record, after her home and office were raided by the City of Marion's entire five-person police department on Friday. Experts believe the extraordinary raid, which was first reported by the Kansas Reflector, was a violation of federal law.

Law enforcement seized her computer, her router, and even the Amazon Alexa speaker she used to stream television shows. On Saturday, reportedly unable to eat or sleep, Meyer collapsed and died.

Many observers would not consider that to be “separate from,” and it’s hard to argue with that point of view. Could it have been truly unfortunate timing? Perhaps. But does it seem likely the immense stress of the ordeal contributed to this woman’s death? It sure seems like it.

The part that stuck out to me was the truly small-town set of events that triggered the whole thing. This was the stuff that I could imagine happening when I was working at a newspaper in a town none too fond of the press.

The saga began on August 1, when Eric Meyer, Joan’s son and the Record's publisher, and Record reporter Phillis Zorn were kicked out of an open forum held by Congressman Jake LaTurner (R-KS) by Marion police chief Gideon Cody. Kari Newell, who owns the coffee shop where the event took place, told Zorn that she "will not have members of the media in my establishment."

On August 7, Newell appeared at the Marion City Council meeting and accused the Record of "illegally obtaining drunken-driving information about her and supplying it to a council member." Newell's accusation, according to Eric Meyer, was false. He reported that "the information was provided to the Record via social media and independently sent… to both the newspaper and the council member."

This accusation was supposedly the basis for the police action, despite any number of reasons that it needn’t raise any concern at all.

Legum continues:

The Record decided not to publish the information. Instead, they alerted Cody because they believed the information might have been obtained improperly. Newell later told Eric Meyer that she believed the information was given to the source by her estranged husband in an effort to sink Newell's pending application for a liquor license. Kansas law prohibits awarding liquor licenses to individuals with felony drunk driving convictions. (Drunk driving is only a felony in Kansas for serial offenders.)

So then what happens? Pretty much what you’d expect.

On August 11, Cody, all four of the city's police officers, and two sheriff's deputies seized computers, cell phones, and other materials from the Record offices, Zorn's home, and the home shared by Eric Meyer and Joan Meyer. The search warrant was extremely broad, authorizing, among other things, the seizure of "digital communications devices allowing access to the internet… which were or have been used to access the Kansas Department of Revenue records website," "documents and records pertaining to Kari Newell," and any "digital store media… used to store documents and items of personal information."

All of this prompted a great outcry from the wider world of media organizations, with all uniformly condemning the actions. And then today, the search warrant was found to be—you guessed it—based on “insufficient evidence” and was accordingly withdrawn and confiscated items to be returned to the paper.

None of this even begins to touch on the police chief’s own potential motives for carrying out the raid, which Legum goes into briefly, citing an interview the paper’s publisher gave to another newsletter.

Why would the police chief conduct a raid on a newspaper's office, its reporters, and its publishers? Cody is very new to the job. He was only sworn in on May 31, 2023. Prior to that, Cody spent 24 years as a police officer in Kansas City, Missouri.

In an interview with Marisa Kabas, author of The Handbasket newsletter, Eric Meyer revealed that the Record "been investigating the police chief." According to Meyer, when Cody "was named Chief just two months ago, we got an outpouring of calls from his former co-workers making a wide array of allegations against him saying that he was about to be demoted at his previous job and that he retired to avoid demotion and punishment over sexual misconduct charges." Notably, "the allegations—including the identities of who made the allegations—were on one of the computers that got seized." Meyer said that one of his reporters had worked for "weeks" on the story. He emphasized that the Recrod is "not making any allegations against him, but we had investigated allegations."

Every single part of this story—the assault on the First Amendment and democracy itself, Meyer’s death, the abuse of power, all of it—is thoroughly depressing. But sadly somehow also just another day?