When Ronan Farrow tweeted the word “stan’ as a verb, I was a bit surprised.

If you’ve ever heard him speak, he’s hyper-articulate, and there’s just something about the word “stan” as it’s been commonly used for the past few years that felt odd to me. As you might remember if you’ve read my posts a few weeks ago on Jia Tolentino, I’m again writing about this person who is ostensibly my contemporary. He was actually born just a few days after I was. But, unlike me, when he turned 11 years old, he was starting college and by 15, he’d be a graduate; at 16, as I was just beginning to drive around rural west Tennessee in a 1993 Jeep Cherokee handed down from my parents, he was beginning at Yale Law School. Followed that up with time working for UNICEF, a stint in the Obama administration, and the State Department under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Oh, and then a Rhodes Scholarship. Oh, and the recent Pulitzer Prize. So when this guy tweeted like everyone else on Twitter tweets, I took notice. And then tried to decide whether I liked it. And couldn’t really tell.

- EXTRA CREDIT: Think of this as a footnote, instead of an interruption to my post, but Farrow’s reporting on MIT Media Lab’s Joi Ito’s connection to Jeffrey Epstein is must-read, top-notch journalism. He, like so many, owe a great deal to the dogged reporting of Julie K. Brown of the Miami Herald.

Here, I’ll confess a certain level of ignorance, of tuning out the current pop cultural discourse: I didn’t actually know where “stan” came from. I only vaguely knew what it meant, and while the definition I could give wouldn’t be wrong, it was clearly the effort of someone groping around in the dark. I don’t know why this was the case; I’d just chosen not to care quite that much, as if never finding out wouldn’t be the worst thing. Surely it was just a Google search away. And it was; my girlfriend looked it up and told me the definition one night on an outdoor patio over dinner.

It came from Eminem, one of the definitive rappers of my adolescence. In 2000, he released “Stan,” a song told as a series of rambling letters to Eminem from an obsessed, stalker-fan — portmanteau-ed into “stan” — named, you guessed it, Stan.

He takes the violence advocated in Em’s lyrics literally, and “Stan” ends with Stan driving his car, which held his wife and daughter in the trunk, off a bridge.

The song was not really describing a new phenomenon, at least not for the likes of Eminem. Elvis Presley was the mold from which Eminem was cast —a supremely talented artist making himself famous for trafficking in a culture and style of music made famous by African Americans — and he couldn’t even be shown below the waist on television due to all the rampaging hormones he might stir up. During this time for Eminem, his discomfort with fame crept into many of his songs, and it was a constant talking point for him. It was understandable. It was relatable, in the most unrelatable of ways. If pressed, could we see where he was coming from, understand why it might suck not to be able to walk outside without fear of mobs or a photographer in the face? Sure, I think we can. But can we really picture it? Can we really separate it from the trappings of fame that we sometimes wish for ourselves? Would we trade our anonymity? Would we regret it as soon as we did?

Michael Schulman wrote a brilliant piece in this week’s New Yorker on superfans. He ends up at San Diego’s Comic-Con, and his piece just captures the randomness of it all — cosplaying fans from Star Wars, Star Trek, Game of Thrones, SpongeBob Squarepants, and more, all hanging out together. There is a groan-inducing sweetness to the whole thing — greater society might write these people off, call them weird, but the thing at Comic-Con is, even when the attendees themselves might feel that impulse, surely something inside them catches and they realize, “There’s no room for me make fun of that guy dressed as Lumiere from Beauty and the Beast because here I am, dressed as Chewbacca.” Or Spock. Or take your pick, because it couldn’t matter less. At least as I picture it, there’s a libertarian ethos underlying Comic-Con; as long as you’re not hurting someone or causing trouble, feel free to be unambiguously you, my friend. And /that/ is startlingly refreshing in this day and age, where outside of Comic-Con, if you were to, say, voice a political opinion, you could be pilloried by any number of community members. That’s where Schulman’s piece begins — the ugly, dark side of fandom, which is tied directly to the internet, and it really shows off the worst of the democratization of publishing and interconnectedness. You’ve heard of all of these ugly moments—Gamergate, Ghostbusters, Game of Thrones, #ReleaseTheSnyderCut.

Circling back to where I started, I’ve come around on the word “stan” mainly because I recognize I am one. I have my fandoms. Just last week, I went to see John Mayer in concert two nights in a row, once in Kansas City and once in St. Louis; they represented the seventh and eight times I’ve seen him perform, respectively. I’ve seen Hamilton three separate times. I rewatch television shows and movies many times over, as my entertainment comfort food. I start far too many sentences with, “I was listening to this podcast, and…” As a concept, I don’t mind that I “stan” certain things. As a word, it still feels younger and cooler than I can pull off.

In a brilliant stroke of magazine planning, Schulman’s fandom piece is followed up immediately with Nathan Heller’s profile of James Gray, the director of the upcoming Ad Astra, starring Brad Pitt.

Gray describes the challenge of writing and directing original material in this age of IP/franchise-laden sequals/prequals/reboots/spin-offs.

“There’s a level of bullshit that the culture is now embracing,” Gray said. “The other day, the doctor is poking around my pancreas, and he’s, like, ‘You see “The Avengers 2”?’ I’m, like, ‘No.’ He said, ‘Why not?’ I’m, like, ‘I’m not nine!’ ” Gray thought that public reporting of movies’ gross profits, a practice that took off in the eighties, changed the popular conception of what a successful film looked like.

As a lover of cinema, I’m on the sideline rooting for the Grays of the industry, hoping beyond hope that they aren’t squeezed out by mega-corporations chasing box office billions.

- EXTRA CREDIT: The Big Picture podcast discusses IP-ness of film industry after the Sony/Marvel spat over the future of Spider-Man, which was another example of superfans acting a fool. The episode concludes with an interview of Ben Berman, the director of The Amazing Johnathan Documentary, which I’ve written about.

Words Matter

In college, I spent a semester interning in Washington, D.C. My roommate was from New York, and he sounded like it. We were a regular Odd Couple, my Southern drawl having met its complete and perfect opposite in him. He was an incredibly smart guy, but that fact lingered beneath the surface because I didn’t think he sounded like he could be particularly bright. As it turned out, I was the one who sounded pretty dumb.

In the midst of a conversation, I said something to the effect of, “Yeah, I like three or four.” His face seemed genuinely perplexed. I couldn’t figure out why. The pause between us grew to an awkward length. He finally asked for clarification. I repeated myself, with the explanation of “You know, I have three or four left to finish…?” He smiles; no, actually it was more of a smirk. “You mean ‘lack’?” Reflexively, I start to say no. But then I actually thought about the phrase I’d uttered. And everything fell apart. My entire life, I’d heard those around me so completely drawl “lack” that the soft A sound morphed into a long I sound, and I’d never once thought critically about it. What the hell would I have even meant if I’d been write and the word should have been “like”? Such was my comeuppance, at the hands of New Yorker. Words matter.

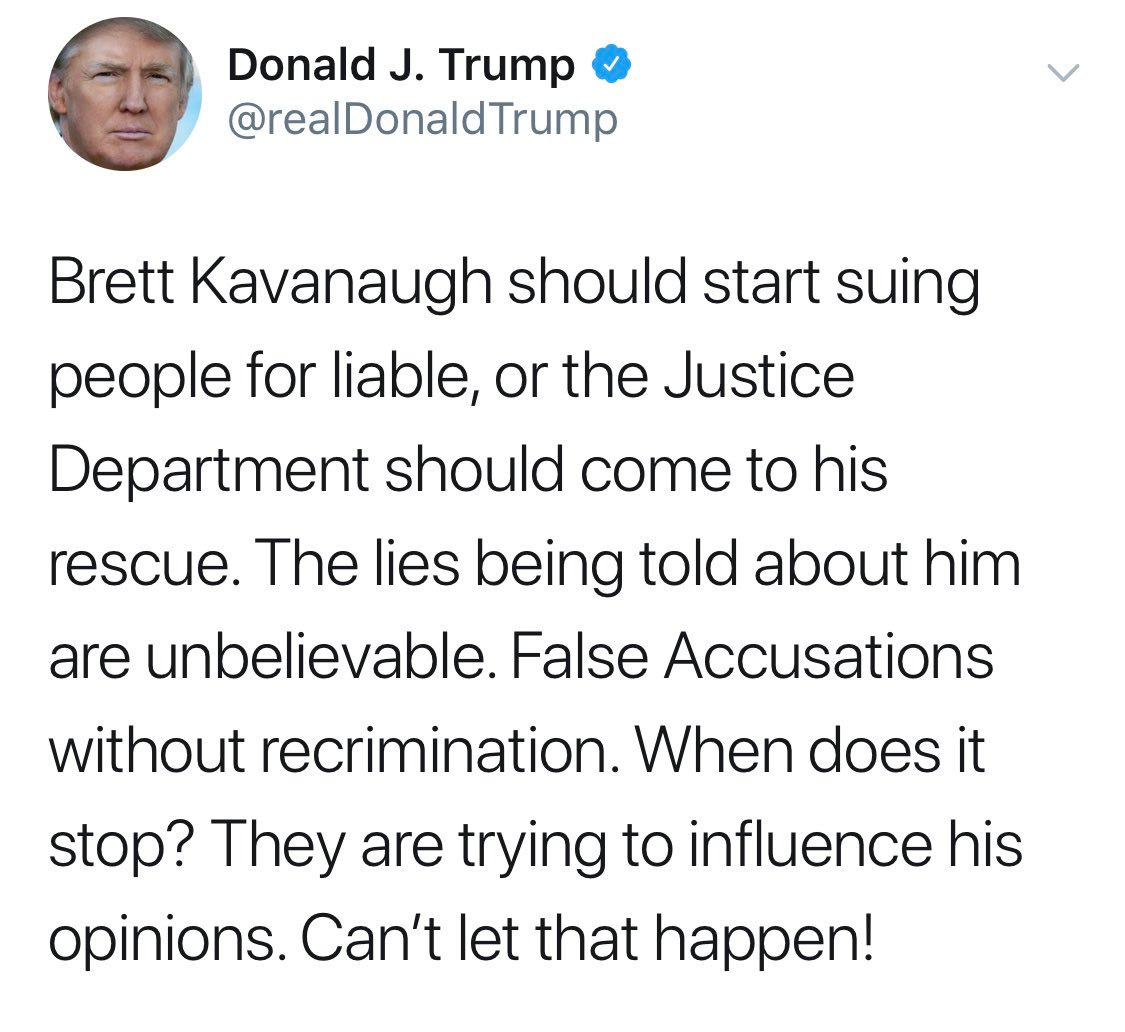

President Trump, a self-describe “very stable genius,” drew the scorn of grammarians with a tweet that showed a lack of understanding of two words that he’s actually heard quite a few times over the course of his life.

As Twitter was quick to remind, “liable” isn’t actually a cause of action; that word would be “libel.”

What prompted Trump’s mistaken tweet? New York Times reporting of another allegation of sexual misconduct from Kavanaugh’s time at Yale. In journalistic terms, the story prompted a lot of discussion because it seems the reporters violated a basic tenet of news reporting: They buried the lead. While journalists were likely the only to care or notice about the lead, the Times then decided to double down on self-sabotage.

After this tone-deaf and offensive tweet went out, the Times now must contend with two sorts of criticism: 1) the usual “who are the people actually making up your newsrooms?” (which is a totally reasonable question) and 2) the handwringing from those who already think they’re fake news and not inclined to listen to them in the first place. The former is constantly needing to be evaluated to improve the quality of the news provided by our nation’s greatest newspaper, but the latter allows for faux outrage and focusing on the screw-up rather than diligent reporting and investigative work that should have been done before Justice Kavanaugh was confirmed.

So, again: Words matter.

Back to the genesis of this issue of the newsletter: the word “stan.” It’s an interesting time to be alive, especially as an aspiring journalist, where the very DNA of the profession is the written word. Even those journos on the radio with buttery-smooth voices and accent-less pronunciations and the perfectly coiffed TV anchors with strong jaws and symmetrical features depend on a written script. Words matter, but how often do we stop to consider them deeply? Outside of my colleagues in the legal world who get paid big bucks to scrutinize over individual words and meanings, it probably doesn’t happen much outside of the media world. But if we stop to consider them for a minute, it opens up a mind-bending line of questions that feel, at times, answerless. Some may truly have no answer. But others do, if you’re just willing to look.

The inimitable writing guru Roy Peter Clark begins his book The Glamour of Grammar with this advice: Read dictionaries for fun and learning. Now, for some, this suggestion lacks a certain appeal. A running joke between with my girlfriend hinges on her assertion that a physical dictionary is pretty much obsolete, and my desperate attempt to prove it serves a greater purpose than something on which she could stand were she ever to need something off the top shelf. To her, this next idea is doubly dumb, but I’m here for it: TWO dictionaries is the way to go. The Oxford English Dictionary to tell us where we’ve been; the American Heritage Dictionary to tell us where we’re going, according to Clark. (If I can’t convince you of the benefit of this, at least follow Merriam-Webster on Twitter; it’s a consistently great account.)

The AHD had what it called a Usage Panel, where learned wordsmiths and lexicographers debate and update our ever-evolving language. The author Michael Lewis (of The Big Short and Moneyball fame) tried his hand at podcasting last year, and it focused on the various types of referees in life. Lewis was a member of the AHD’s Usage Panel, and discusses language and dictionaries and grammar and usage with one Bryan Garner. Check out the episode here:

Against the Rules—Ep. 3 The Alex Kogan Experience

In his examples of disputes the panel would be called on to settle, Lewis mentions the word “unique” and reminds us that something can’t be “very unique.” I learned that lesson from Aaron Sorkin’s The West Wing (hear me when I say I stan Sorkin and The West Wing). Watch the entire clip to see many aspects of what made the show great (intricate walk-and-talks filmed to perfection, snappy dialogue, idealism in the White House), but if you’re only interested in the grammar lesson, it starts at 2:40.

Garner is the author of Modern English Usage, a one-stop shop of guidance for all things related to writing/speaking the English language. An earlier version of his book was reviewed by the noted grammarian and wordsmith David Foster Wallace, originally published in Harper’s and the reformulated for inclusion in Consider the Lobster. Wallace considers the concept of our language and usage conventions. He describes the schism between lexicographers on the Prescriptivists, who tell us how language should be used, and the Descriptivists, who tell us how language is actually used. The essay is a testament to Wallace’s power as a writer, as he makes a book review (a genre susceptible to charges of “boring”) of a dictionary (likewise, not the sexiest material) an interesting and thought-provoking analysis on how we speak, why we speak how we speak, and how we should consider teaching how we speak.

For love of dictionaries (and great storytelling), check out Longform’s episode with Jack Hitt. A veteran writer, Hitt is simply an amazing talker. You don’t have to be a lover of great journalism to enjoy his stories. When he was trying to break into journalism, he took a bus to the only newspaper editor that responded to his letters, and over lunch, he told the editor that his father had memorized the dictionary and he was trying it, too. The editor said he’d memorized the dictionary as well, and then asked Hitt if he had a favorite word. Hitt did; it was “callipygous.” Look it up.

This entire conversation makes me think not just about the internetification of our language, but of how we seek knowledge. There is an exploratory element to knowledge acquisition that has been greatly reduced by the exactitude of a Google search bar and its hierarchical results. You know what you want to find out, so you type that and only that into the search bar, and voila. You’re that question wiser now. But back when the dictionary or encyclopedia were the primary resources, you often had to learn much more than just the information you were seeking. It was a necessity. To find what you needed, you would have to sift through that which you didn’t. Those of us in a hurry celebrate the speed of Google, but the part of us that lives on as a curious species is suffering. It happens far less frequently now, but that’s not to say that it doesn’t happen. It’s sometimes shocking how far afield you can be led by hyperlinks in a Wikipedia article. And sometimes we let ourselves be taken on that wild ride, and I’d argue we’re all the better for it. In support of this curiosity, let me recommend two books:

- The Know-It-All. Writer A.J. Jacobs wrote this book as part journal, part history when he decided to read every word of the Encyclopedia Britannica. The book is structured like an encyclopedia itself, with entries written in alphabetical order and relaying a mixture of genuinely interesting information and Jacobs’ wit.

Jacobs describes the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica as the gold standard, and Denis Boyle’s Everything Explained That Is Explainable: On the Creation of the Encyclopedia Britannica’s Celebrated Eleventh Edition, 1910-1911 goes into that history much more deeply.

If you’ve liked this content, please do two things for me: 1) sign up for the newsletter by entering your email address, and 2) please forward this to all those in your address book that would appreciate it as well and tell them to sign up. Thanks so much for reading.