Whitehead's Repeat

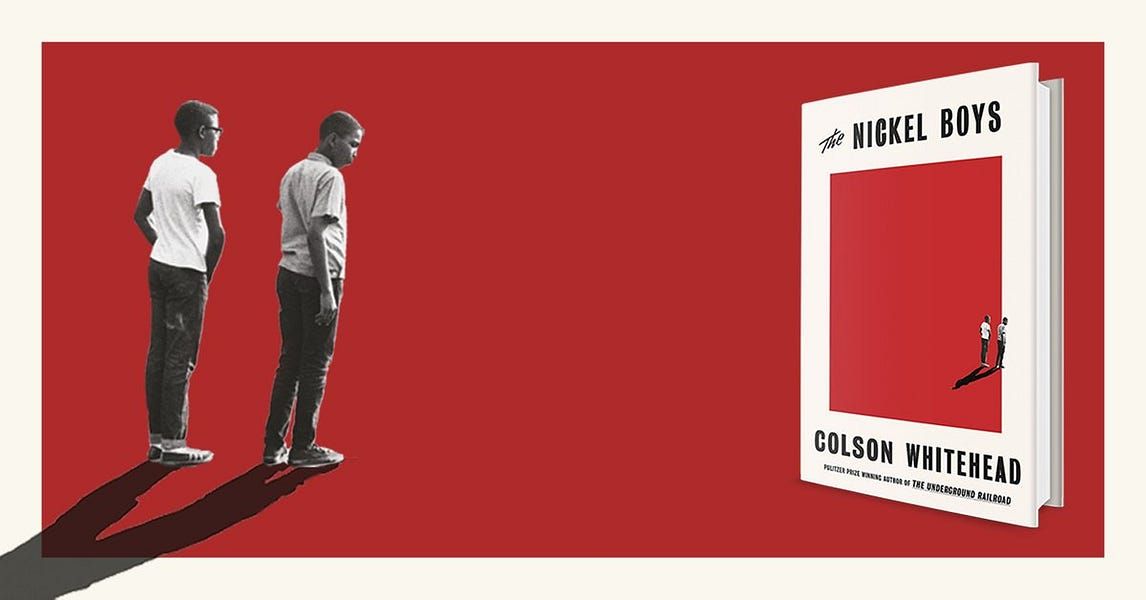

Author Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize last week for his latest novel. You should read it ASAP.

I want to sing the praises of another Pulitzer Prize winner from last week, as I hadn’t finished it by week’s end. Colson Whitehead’s newest novel, The Nickel Boys, is a beautifully rendered yet heart-wrenching tale of a Jim Crow-era Florida reform school for boys, the violence and dehumanization that took place there, and the effect on those who survived their imprisonment.

The Nickel Boys is fiction, but it was inspired by a gruesome reality unearthed in 2014 as college archeology students dug up some long-buried secrets. The New York Times’ review of the novel begins this way:

Though the story had been hiding in plain sight for decades, it was not until 2014 that Colson Whitehead stumbled upon the inspiration for his haunted and haunting new novel, “The Nickel Boys.” As he explains in his acknowledgments, he learned through The Tampa Bay Times about archaeology students at the University of South Florida who were digging up and trying to identify the remains of students who had been tortured, raped and mutilated, then buried in a secret graveyard, at the state-run Dozier School for Boys in the Panhandle town of Marianna. Dozier’s century-plus reign of terror ended only in 2011, and graves were still being discovered after Whitehead’s novel went to press. New evidence disinterred in March may raise the fatality count above 80. We will never learn the exact number, any more than we will ever have a full accounting of all the other hidden graves where crushed black bodies have been disposed of like garbage since the birth of the nation.

I remember the book’s release last summer; I remember the acclaim and excitement over it. But most of all I remember an episode of NPR’s Fresh Air on which Whitehead discussed the book at length. I remember listening to it in the car on the road between Columbia and Springfield. I don’t remember when I was listening, but I remember the exit from Hwy. 5 onto Hwy. 54 as Whitehead read from the early pages of the novel, of the survivors returning to the school for a reunion:

The annual reunion, now in its fifth year, was strange and necessary. The boys were old men now, with wives and ex-wives and children they did or didn't talk to, with wary grandchildren who were brought around sometimes and those whom they were prevented from seeing. They had managed to scrape up a life after leaving Nickel or had never fit in at all with normal people - the last smokers of cigarette brands you never see, late to the self-help regimens, always on the verge of disappearing, dead in prison or decomposing in rooms they rented by the week, frozen to death in the woods after drinking turpentine.

The men met in the conference room of the Eleanor Garden Inn to catch up before caravanning out to Nickel for the solemn tour. Some years, you felt strong enough to head down that cement walkway, knowing that it led to one of your bad places. And some years, you didn't - avoidable or stared in the face, depending on your reserves that morning.

The novel’s main character is named Elwood Curtis, and I’ll let Whitehead’s description from the Fresh Air interview speak for itself:

His name is Elwood Curtis. He's a straight-A student being raised by his grandparents. You know, has a job after school working in a tobacco store, wants to go to college. And he's grown up idolizing Martin Luther King and all the lights of the civil rights movement. He reads Life magazine every week and sees the updates on the boycotts and protests and sit-ins and sees himself as a part of this new generation that's going to change America, you know, bit by bit.

In the cruelest of ironies, it’s Elwood’s stand-up character that led him to his stint in Trevor Nickel Academy. He’s approached by a high school teacher with a great opportunity – to take college classes for free while still in high school. He’s only being offered the chance because he’s so noticeably different from his classmates; he’s so good, so pure. The college is seven miles away, and he’s walking the distance because his bike chain has been messed up since he was jumped by some neighborhood boys for stopping them from stealing from the tobacco store in which he worked. He decides to hitchhike, and he’s picked up by a man who, unbeknownst to him, had stolen the car. They were pulled over, and all of Elwood’s grand plans were upended as he was sentenced to the reform school.

The novel succinctly delivers the reader to the school’s campus, divided between the white and black sides as segregation is practiced like a microcosm of the outside world. It educates the reader quickly in the rituals and idiosyncracies of the place, from how meals are administered to how punishment is meted out. So much happens in such a short amount of space; The Nickel Boys would be an excellent modern addition to a literature course’s syllabus under the heading of “Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory.” Whitehead does not drag out any aspect of the story; vast swaths of time pass in mere sentences. But when and where he chooses to focus is so vivid, so raw and visceral, that one can’t help but fill in the blanks of the various days of Elwood’s existence that go by without comment.

The biggest moment of the book happens in such a subtle, restrained way that I sped right past it upon first reading. A page or two later, I was forced to flip back and reread it again before I fully understood what had happened, and then it just settled on me: an entirely new way to consider what I’d read up to that point. It was a magical experience, to have my eyes opened for the first time so deep into the story. It’s no wonder that this novel made Whitehead only the fourth writer to win a second Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Do yourself a favor and buy it today (support a local independent bookstore if you can). Until then, enjoy the interview with NPR’s Dave Davies on Fresh Air and Frank Rich’s New York Times’ review.

Colson Whitehead On The True Story Of Abuse And Injustice Behind 'Nickel Boys' | NPR’s Fresh Air

In ‘The Nickel Boys,’ Colson Whitehead Depicts a Real-Life House of Horrors | The New York Times

If you liked what you read, please sign up, follow me on Twitter (@CaryLiljohn06) and then forward to friends to help spread the word.