Y'all...should really read this story

"Y'all" isn't just my preferred way to address a group; it's actually a clue to solve a mystery. Take a break from the virus and read some truly great writing.

There are few things that can take your mind off what’s going on out in the real world more effectively than a brilliantly told story. Sometimes the facts of the story are so compelling that even Charlie Brown’s teacher could make it sound interesting. Other times it’s the writer’s mastery of language, of plotting and structure, of timing, of scene setting, of dialogue, of details, of creating a world into which you can lose yourself. And blessed few times, far too few, you get both – a truly “what the hell” story told by an incredibly gifted storyteller.

Just such a story was published yesterday by The New York Times Magazine. It was written by author/journalist/professor of creative nonfiction, Sarah Viren. The story is a first-persona account from inside a fabricated sexual misconduct allegation that led to Title IX investigations of both Viren and her wife Marta.

Reading that email, I remembered the year I arrived in Iowa. All the local newspapers were reporting on a professor who was accused of requesting sexual favors from students in exchange for higher grades. When confronted, he drove out to the same woods where I ran each morning and shot himself. I tried to imagine Marta in his place, asking to touch or kiss students in exchange for a grade. But I couldn’t do it. I know many spouses of sexual criminals say this, but I was sure: She just wasn’t the type.

This essay will likely be all over the Internet, certainly to be one of the most-read stories of the year that doesn’t contain the words “Trump” or “coronavirus.” But it should go into the files of journalism professors and writing instructors across the country as a masterclass in structure.

I’m not simply describing the narrative profluence, which John Gardner described in The Art of Fiction as the forward push of the story, the page-turning quality, if you will. This essay is charging, sprinting in nature; you cannot stop yourself from reading to answer the ever-present question of “What happened next?” Viren’s words should be studied and appreciated for that element, and she no doubt built up those muscles as a reporter.

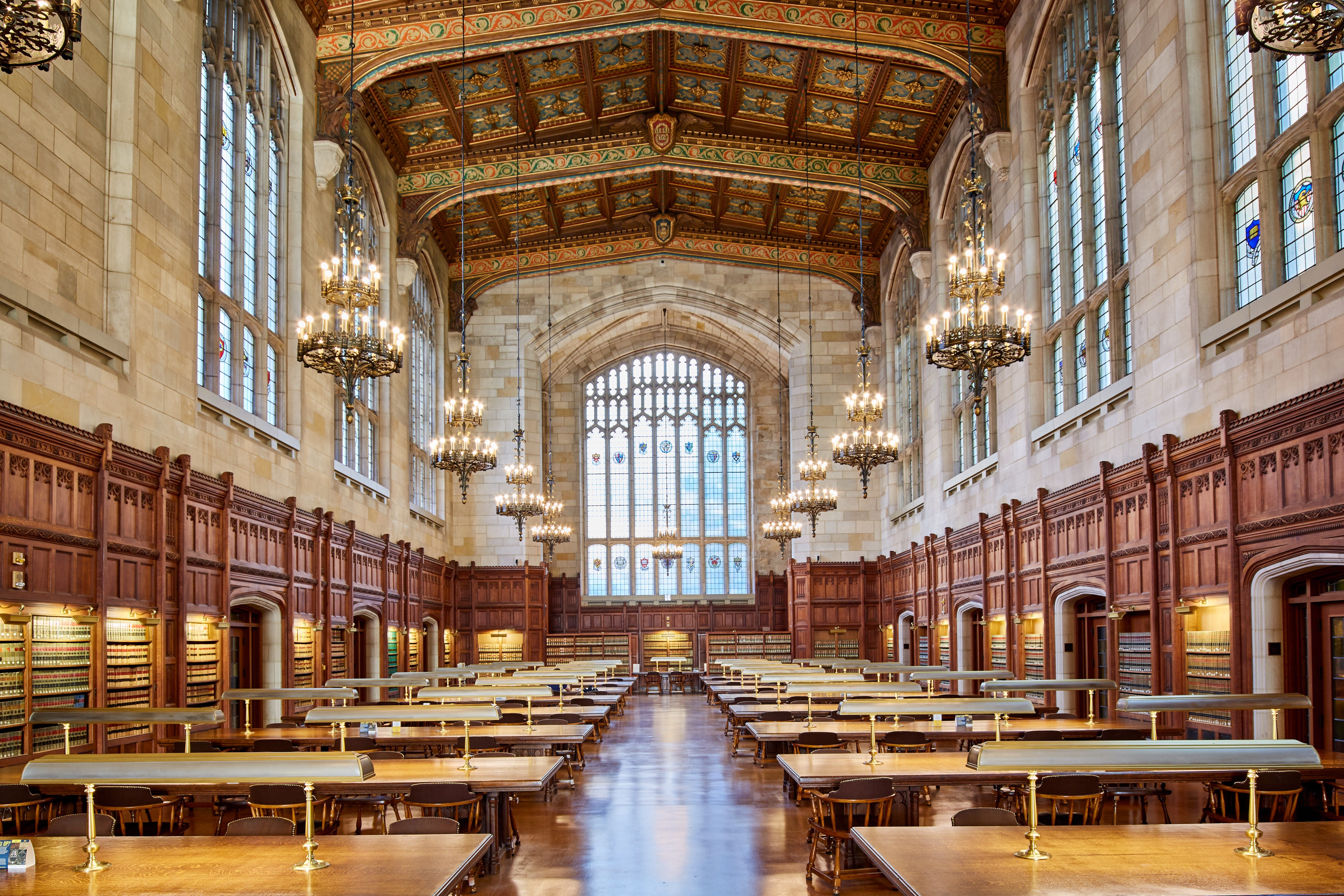

Photo by Mathew Schwartz on Unsplash

The structural genius of this essay lies in a small, easily forgettable moment from Viren’s past. Early in the story, she sets up the nature of academic job searches, and she uses this process to reveal, bit by bit, how she came to learn of the allegations against, first, Marta, and then herself. But about a third of the way into the essay, she backtracks even further, to the first time she’d ever gone through the academic job search process.

The first time I went on the academic job market was during the 2016 election. I sat for a Skype interview only a month and a half after giving birth to F., and only a month after Donald Trump was elected president. I was still bleary-eyed and foggy-headed from the birth and the lack of sleep that followed, and one interviewer asked me, given the recent crisis regarding fake news and alternative facts, what responsibility I thought writers of creative nonfiction had toward our collective understanding of truth.

My answer meandered into platitudes about truth being subjective and facts being contingent; I wasn’t invited to a campus visit for that job. But I’ve thought about that question a lot since then and how I might have answered it better.

A true story written about Marta and me at this point could easily include all the facts we know right now: that complaints were made about Marta, that Reddit posts appeared and that an investigation was opened. And if I were to read a story like that — without knowing Marta or me or any other facts that came to light later — I would conclude either that Marta had done it or, at the very least, that she was the kind of professor who crossed the line, and that her actions had been misconstrued. I would assume, that is, that even if some of the facts were wrong, the truth lay somewhere in the middle.

In the course of reading this story, with these few paragraphs in your rearview but before you’d reached the conclusion, you’d be forgiven if you’d forgotten about them. But when you reach the conclusion, they come roaring back to the fore, and you realize they were not merely tossed off in the middle of the essay to make a small but unnecessary point. No, they are actually the very lens through which you’re meant to view the entire thing. And it is beautiful.

Read every perfectly crafted paragraph here:

The Accusations were lies. But could we prove it? | The New York Times Magazine

Dive Deeper

Once I read this story, I immediately sought out more by Viren. This essay for the Times is no one-off. I particularly liked an essay that was published in The Pinch, the literary journal published by the MFA program at my alma mater, The University of Memphis. Come for the enticing title, stay for more insightful and beautifully rendered first-person writing.

My Murderer’s Futon | The Pinch

If you liked what you read, please sign up, follow me on Twitter (@CaryLiljohn06) and then forward to friends to help spread the word.