In Praise of the Book Section

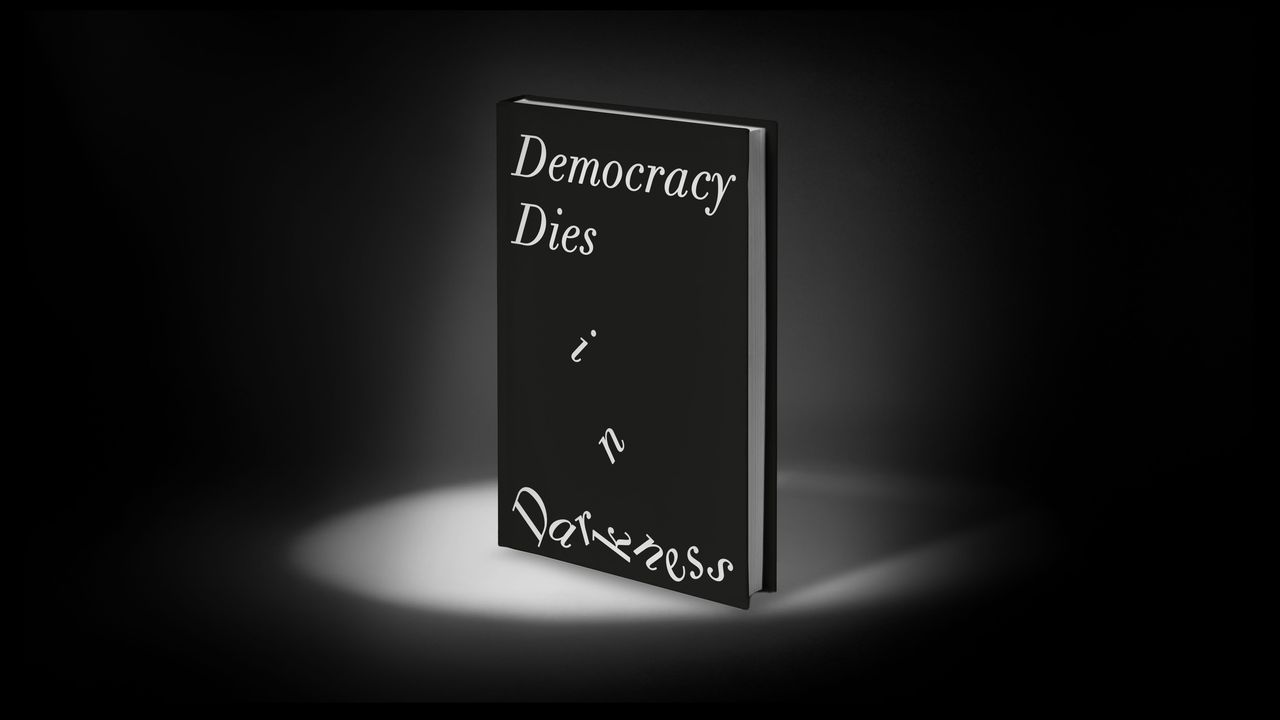

I've been doom-reading (and listening) to lots and lots of commentary around the gutting of The Washington Post. If you're unaware, last week the paper fired 300 journalists, en masse, in what very well may have been the single largest instance of journalism-job slashing ever committed.

I'm a longtime subscriber of the Post's digital product, and if I'm being honest, no, I don't turn to it nearly as often as I do the New York Times. (And no, that's not because I'm opening the Times app for the games. First of all, how dare you? Second of all, I have the dedicated games app, so when I open NYT proper, it's for the news.)

But one of the things I regularly checked in on was the paper's books coverage.

Partly to get recommendations, partly to stare longingly through the department-store window at a career I wish I could have: Read interesting books and get paid to write compelling pieces of criticism that recapped my experience while reading said books. That's the dream.

I really loved this piece in The New Yorker by Becca Rothfeld, who'd previously decamped from the Post.

It's not just because she speaks lovingly of the work she did at the paper (though she does and I loved every tiny detail); it's because she sings the praises of what a book section (and newspapers and magazines, more generally) provide to the reader, especially in these algorithm-driven lives we now inhabit.

In the three years that I worked at the Post, I fielded mail from all manner of people—doctors, teachers, prison inmates, and, not infrequently, Ralph Nader—about reviews I had written of everything from Senator Josh Hawley’s book about masculinity to the letters of Gustave Flaubert. Readers wrote from the D.C. suburbs and the Netherlands, from Arizona and New York. What they often evinced was better than interest, better even than bibliophilia; it was the rare and precious capacity to be interested in what they didn’t already know interested them. It was a willingness to be changed.

And perhaps more powerfully:

A newspaper is—or ought to be—the opposite of an algorithm, a bastion of enlightened generalism in an era of hyperspecialization and personalized marketing. It assumes that there is a range of subjects an educated reader ought to know about, whether she knows that she ought to know about them or not. Maybe she would prefer to scroll through the day-in-the-life Reels that Instagram offers up to her on the basis of the day-in-the-life Reels that she watched previously, and so much the worse for her. The maximalism and somewhat uncompromising presumption of a newspaper, with its warren of sections and columns and byways, is a quiet reproach to its audience’s most parochial instincts. Its mission is not to indulge existing tastes but to challenge them—to create a certain kind of person and, thereby, a certain kind of public.

It heartens me to know there is a dedicated segment of people who feel this way; if only there were enough money and opportunities for all of them find work. One of the signature publications in journalism — the kind of spot where people could let out a big sigh that said "I made it" before getting back to the grind necessary to maintain their place — just made that even harder, and we're all the poorer for it.

Comments